1. INTRODUCTION A catchment's water yield is a fundamental problem in hydrology, referring to the volume of water available at the catchment outlet over a specified period of time. The yield is expressed for monthly, seasonal, or annual periods. Several approaches are available for the computation of water yield. These vary in complexity from simple empirical formulas to complex models based on continuous simulation. While the empirical formulas have limited applicability (Sutcliffe and Rangeley, 1960; Woodruff and Hewlett, 1970), the continuous simulation models require large amounts of data for their successful operation (Crawford and Linsley, 1966). A practical alternative is represented by conceptual models which use the water balance (or hydrologic budget) equation to separate precipitation into its various components (Hamon, 1963). In this paper, we develop a conceptual model of annual water balance, suitable for application to a wide range of climatic conditions. The model separates annual precipitation into its three major components: surface runoff, baseflow, and vaporization. It is based on a two-step sequential application of a proportional relation linking two variables X and Y, such that the difference Z = X - Y asymptotically reaches an upper bound as X and Y grow unbounded. The generic form of the proportional relation has two parameters: λ, the initial abstraction coefficient, and Zp, the potential value of Z = X - Y. Initial testing using L'vovich's (1979) catchment data shows that the model is applicable throughout a wide range of climatic settings.

2. WATER BALANCE EQUATIONS A water balance equation applicable to an individual storm is:

in which P is precipitation, Q is surface runoff (also rainfall excess), and L is losses, or hydrologic abstractions (in millimeters, centimeters, or inches). The losses for an individual storm consist of interception, surface storage, and infiltration. A water balance equation applicable on an annual basis is:

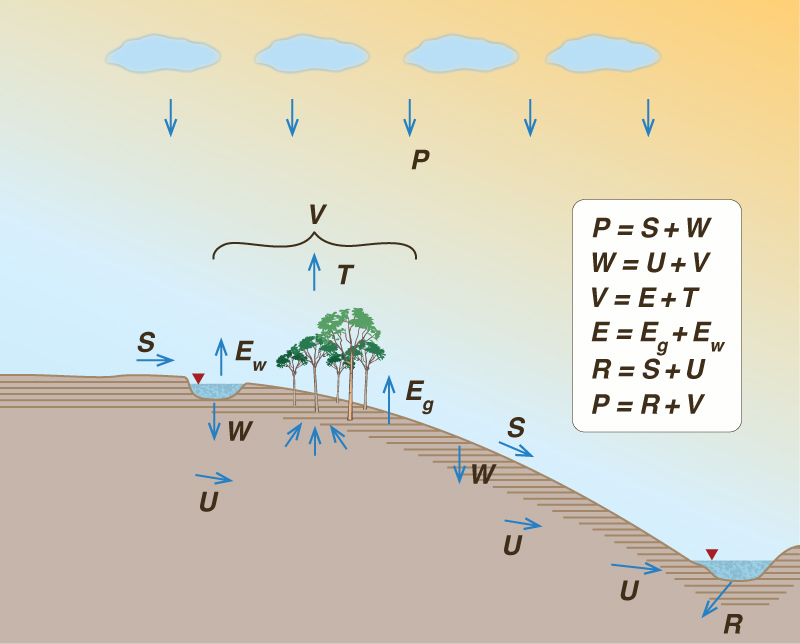

in which P is precipitation, R is runoff, including surface and subsurface runoff, and E is evapotranspiration (in millimeters, centimeters, or inches). In this equation, the term 'evapotranspiration' comprises all three types of evaporated moisture: (1) evaporation from vegetated surfaces, i.e. evapotranspiration, (2) evaporation from nonvegetated surfaces (bare ground), and (3) evaporation from water bodies. Equations 1 and 2 are highly simplified models of a segment of the hydrologic cycle. For example, Eq. 1 does not describe the portion of surface storage that may eventually infiltrate into the ground. Likewise, Eq. 2 does not explicitly describe soil moisture, which is included in both runoff and evaporation. In fact, as shown by L'vovich (1979), a catchment's annual water balance is better described by a set of equations. Annual precipitation P may be separated into two components (Fig. 1):

where S is surface runoff, i.e. the fraction of runoff originating on the land surface, and W is catchment welting, or simply 'wetting', the fraction of precipitation not contributing to surface runoff. (Note that Eq. 3 is the annual equivalent of Eq. 1.)

Likewise, wetting consists of two components:

where U is baseflow, i.e. the fraction of wetting which exfiltrates as the dry-weather flow of rivers, and V is vaporization, the fraction of wetting returned to the atmosphere as water vapor (Lee, 1970). Deep percolation, i.e. the portion of wetting not contributing to either baseflow or vaporization, is a very small fraction of precipitation [a global average of less than 1.5%, according to L'vovich (1979)], and is neglected here on practical grounds. Vaporization, which comprises all moisture returned to the atmosphere, has two components:

where E is nonproductive evaporation, hereafter referred to as 'evaporation', and T is productive evaporation, i.e. that resulting from plant transpiration, hereafter referred to as 'evapotranspiration.' Evaporation has two components: (1) En, evaporation from nonvegetated areas of the Earth's surface and near-surface, i.e. from bare soil and small surface storage (puddles); (2) Ew, evaporation from sizable water bodies such as lakes, reservoirs, and rivers. Evapotranspiration is the evaporation from vegetated surfaces such as leaves and other parts of plants, a function of the physiological need of plants to pump moisture from the soil to maintain turgor and avail themselves of nutrients. From Eqs. 3, 4, and 5, runoff consists of two components:

Likewise, precipitation P consists of two components:

Equation 7 is analogous to the well-known annual water balance Eq. 2. However, Eq. 7 is preferred here, because the term 'vaporization' clearly identifies the three sources of evaporated moisture The set of Eqs. 3-7 constitute a set of water balance equations. Combining Eqs. 6 and 7 leads to:

that is, annual precipitation is separated into its three major components: surface runoff, baseflow, and vaporization. Significantly, Eq. 8 assumes that the change in soil-moisture storage from year to year is negligible, an assumption which is useful as a first approximation. Equations 4 and 7 allow the definition of water balance coefficients. The baseflow coefficient is (L'vovich, 1979):

and the runoff coefficient is:

These coefficients vary as a function of prevailing climate, theoretically within the range 0-1. 3. THE CONCEPTUAL MODEL A significant feature of the water balance equations (Eqs. 3-7) is that they all have the same structure, in which a quantity X is expressed as the sum of two components Y and Z:

L'vovich (1979) has shown that Eq. 3 can be modeled by a proportional relation such that wetting asymptotically reaches an upper bound (W → Wp) as precipitation and surface runoff increase unbounded (P → ∞; S → ∞). It is noted that a similar relation is the basis of the SCS runoff curve number model, which solves Eq. 1 (US Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service (USDA SCS), 1985). L'vovich (1979) has also shown that Eq. 4 can be modeled by the same type of relation, i.e. one where vaporization reaches an upper bound asymptotically (V → Vp) as wetting and baseflow increase unbounded (W → ∞; U → ∞). In this way, the sequential two-step separation of annual precipitation into its three major components, surface runoff, baseflow, and vaporization, is accomplished. The generic form of the proportional relation is, according to the SCS model (USDA SCS, 1985),

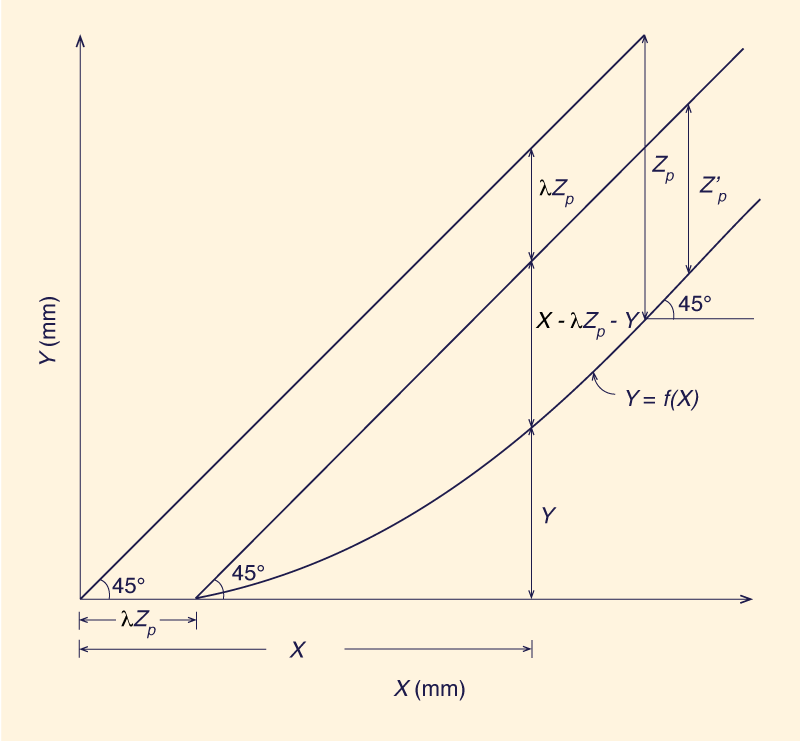

in which Y = f(X) and λ' is the initial abstraction coefficient. The initial abstraction is Ia = λ' Zp', in which Zp' is the potential value of Z', i.e. an upper bound to Z' = X - λ' Zp' - Y. In this paper, the initial abstraction is alternatively defined as Ia = λ Zp in which Zp is the potential value of Z = X - Y (Fig. 2). This leads to a slightly modified form of the proportional relation:

Equation 13 has a significant advantage over Eq. 12. Unlike λ', which has no theoretical upper bound, λ is limited in the range 0 ≤ λ ≤ 1. The initial abstraction coefficient λ is dimensionless; the units of Zp are those of X and Y (millimeters, centimeters, or inches). For the special case of zero initial abstraction (λ = 0), Eq. 13 reduces to:

Solving Eq. 13 for Y = f(X) leads to:

subject to X > λ Zp; Y = 0 otherwise. Using Eq. 15, the surface runoff submodel is:

subject to P > λsWp, and S = 0 otherwise, where λs is the surface-runoff initial abstraction coefficient. From Eq. 3,

Likewise, the baseflow submodel is:

subject to W > λu Vp, and U = 0 otherwise, where λu is the baseflow initial abstraction coefficient. From Eq. 4,

Thus, given annual precipitation and a set of initial abstraction coefficients λs and λu and potentials Wp and Vp, Eqs. 16-19 are used to separate annual precipitation into surface runoff, baseflow, and vaporization. Then, runoff is calculated by Eq. 6, and the baseflow and runoff coefficients Ku and Kr are calculated using Eqs. 9 and 10, respectively. 4. MODEL CALIBRATION In the absence of data, the initial abstraction coefficients and potentials are estimated from past experience in similar climatic settings. When data are available, the model parameters can be calibrated. For λ = 0, Zp is solved from Eq. 14:

For λ > 0, Zp is solved from Eq. 13:

To calibrate the model parameters based on X-Y data, the following recursive procedure is suggested:

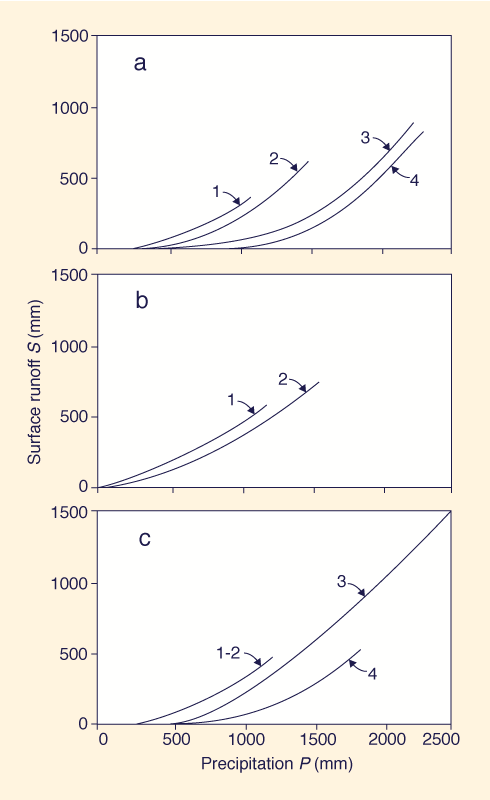

The calibrated λ is that for which the coefficient of variation of the Zp array is a minimum. This procedure was applied to L'vovich's catchment data (1979), and the results of the calibration are shown in Tables 1 and 2. On the basis of this initial application, a tentative classification of parameter ranges is suggested: initial abstraction coefficient λ (dimensionless): low (0 < λ ≤ 0.1), average (0.1 < λ ≤ 0.3), high (0.3 < λ ≤ 0.5), and very high (0.5 < λ ≤ 1); potential Zp (mm): low (0 ≤ Zp ≤ 1000), average (1000 < Zp ≤ 3000), high (3000 < Zp ≤ 5000), and very high (Zp > 5000). Table 1 shows calibrated values of surface-runoff initial abstraction coefficient λs and wetting potential Wp for nine P - S data sets included by L'vovich (1979) (Fig. 3). Analysis of Table 1 leads to the following conclusions:

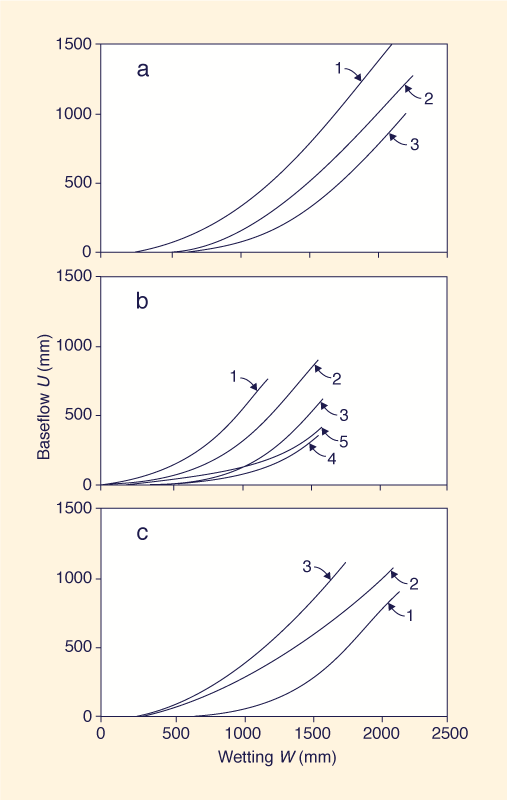

Table 2 shows calibrated values of baseflow initial abstraction coefficient λu and vaporization potential Vp for 11 W - U data sets included by L'vovich (1979) (Fig. 4). Analysis of this table leads to the following conclusions:

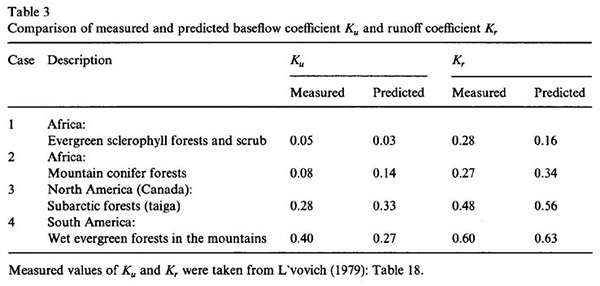

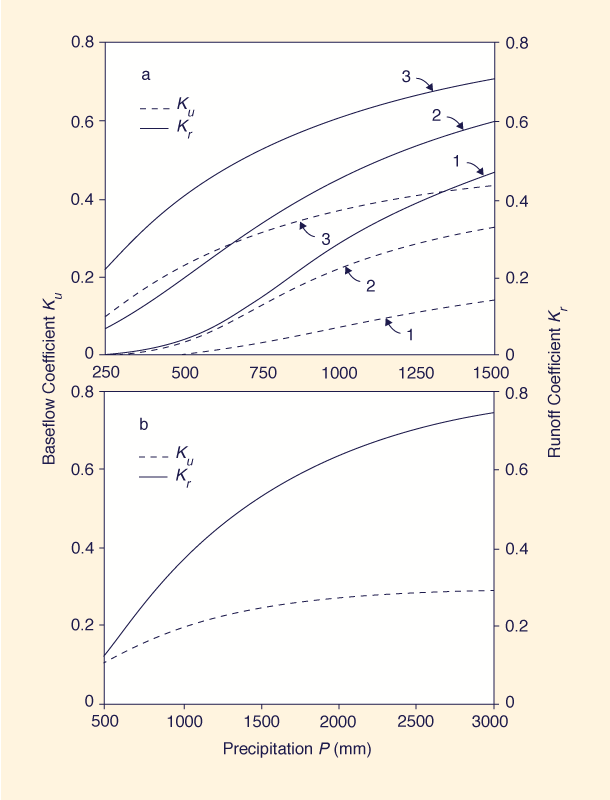

Table 3 shows a comparison of baseflow and runoff coefficients reported by L'vovich (1979) and predicted by the conceptual model developed herein. It is seen that the conceptual model is reasonably predictive for a wide range of climatic conditions. Figure 5 shows calculated baseflow and runoff coefficients for selected biogeographical-climatic regions shown in Table 3. It is seen that the coefficients predicted by the conceptual model are responsive to variations in precipitation input.

The wetting potential Wp is an upper bound to the fraction of annual precipitation that can be retained by a given catchment. A typical catchment is likely to feature several areas, each with a wetting potential Wpi covering a partial area Ai. A wetting potential spatially weighted for the entire catchment is:

The vaporization potential Vp is an upper bound to the fraction of annual wetting that can evaporate from a given catchment. A typical catchment is likely to have three distinct types of surfaces:

5. SUMMARY

A conceptual model of a catchment's water balance is formulated. The model is based on the sequential separation of annual precipitation into surface runoff and wetting, and wetting into baseflow and vaporization. The separation is based on a proportional relation linking the three variables involved at each step. The generic form of the proportional relation is Given a set of model parameters, the model can separate annual precipitation into its three major components: surface runoff, baseflow, and vaporization. Furthermore, baseflow and runoff coefficients are characterized as a function of climate. The model can be used for estimates of annual water yield throughout the climatic spectrum. An initial application of the model to L'vovich's (1979) catchment data provided encouragjng results. Additional research is needed to determine initial abstraction coefficients and potentials for a wide range of associated biogeographical regions and climatic settings. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The present study was performed in Spring 1994, while A.V. Shetty was at San Diego State University, on leave from the Hard Rock Regional Centre, National Institute of Hydrology, Belgaum, Karnataka, India. His leave was funded by the United Nations Development Programme. REFERENCES

Crawford, N. H. and R. K. Linsley. 1966. Digital simulation in hydrology: the Stanford watershed model IV. Stanford Univ. Dep. Civ. Eng. Tech. Rep. 39.

Hamon, W.R. 1963. Computation of direct runoff amounts from storm rainfall. Int. Assoc. Sci. Hydrol. Publ., 63: 52-62.

Lee, R. 1970. Theoretical estimates versus forest venter yield. Water Resour. Res., 6(5): 1327-1334.

L'vovich, M. I. 1979. World water resources and their future. Original in Russian. English translation, American Geophysical Union, Washington, DC.

Sutcliffe, J. V. and W. R. Rangeley. 1960. Variability of annual river flow related to rainfall records. Int. Assoc. Sci. Hydrol. Publ., 76: 182-192.

U.S. Department of Agriculture Soil Conservation Service (USDA SCS). 1985. National Engineering Handbook, Section 4: Hydrology. SCS, Washington, DC.

Woodruff, J. F. and J. D. Hewlett. 1970. Predicting and mapping the average hydrologic response for the Eastern United States. Water Resour. Res., 6(5): 1312-1326.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 211229 |

| Documents in Portable Document Format (PDF) require Adobe Acrobat Reader 5.0 or higher to view; download Adobe Acrobat Reader. |