|

|

|

CHAPTER 8: CULVERT HYDRAULICS |

8.1 CULVERTS

|

|

Culverts are hydraulically short drainage conduits placed in locations where the drainage network intersects the transportation network (roads, railroad tracks). Culverts differ from bridges in that they are much smaller; thus, there are many more culverts than bridges. Culverts are designed to operate under gradually varied flow; therefore, the principles of Chapter 7 are applicable.

Culverts are designed to pass the design

discharge without overtopping of the superstructure.

The design discharge is derived from the

design storm,

which is based on hydrologic considerations.

The return period

of the design storm, i.e.,

the reciprocal of the frequency,

typically varies from

10 to 50 years. The choice of return period has been

elaborated by Ponce (2008).

The longer the return period, the

greater the design discharge and, therefore,

the larger the required culvert size

|

The flow in a culvert is a function of:

Cross-sectional size and shape,

Bottom slope,

Barrel length,

Roughness, and

Entrance and exit characteristics.

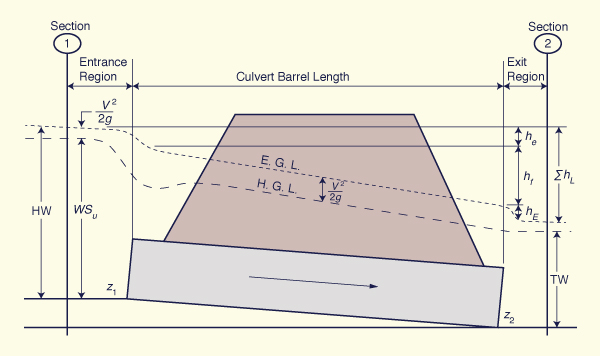

The flow in a culvert may be either (a) completely free-surface (open-channel flow), (b) completely closed-conduit (pipe flow), or (c) partially free-surface and closed-conduit flow. Headwater (HW) is the depth of water above the culvert invert at the inlet. Tailwater (TW) is the depth of water above the culvert invert at the outlet. The design headwater and tailwater elevations are major factors in determining whether the culvert flows partially full or completely full.

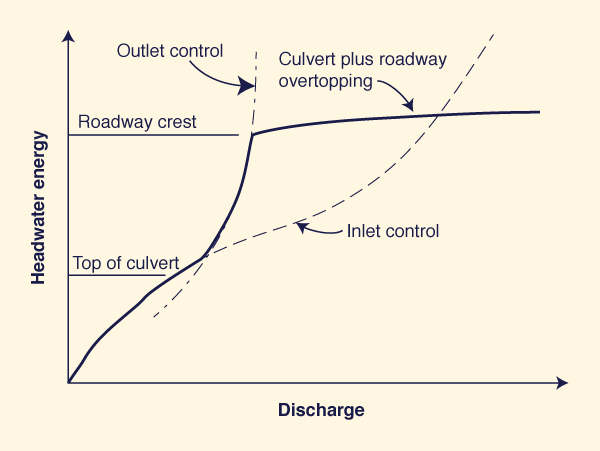

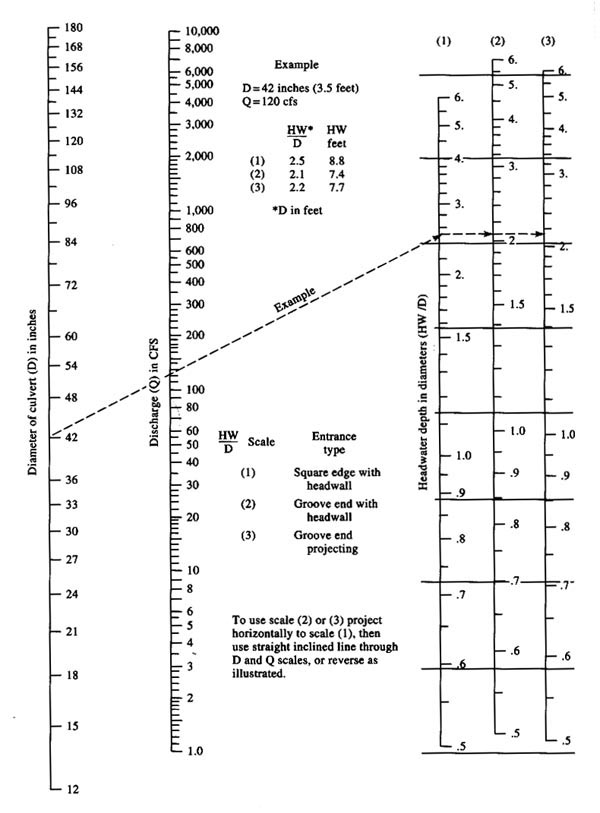

The design objective is to find the most economical design (i.e., the smallest culvert size) that will pass the design discharge without exceeding a specified headwater elevation (Fig. 8-2). The design depends on whether the culvert flow is under: (a) inlet control, or (b) outlet control.

|

8.2 INLET CONTROL

|

|

Culvert flow is under inlet control when the discharge depends only on the conditions at the inlet. For example, assume a circular culvert of diameter D, length L, slope S, headwater depth HW, and tailwater depth TW.

The first step is to calculate the normal depth yn and the critical flow depth yc . Then, the following situations are examined:

If yn < yc , the flow in the culvert barrel is supercritical and the tailwater has no influence on the upstream conditions (Fig. 8-3). Therefore, the headwater is solely controlled by the conditions at the inlet.

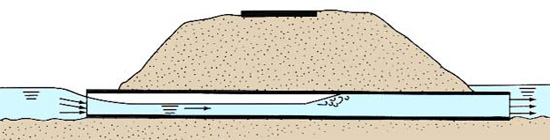

Fig. 8-3 Culvert flow under supercritical conditions, with inlet submerged

and outlet unsubmerged.If the flow is supercritical and the TW > yn, a hydraulic jump may form at or near the culvert outlet (Fig. 8-4).

Fig. 8-4 Culvert flow under supercritical conditions, with inlet unsubmerged

and outlet submerged due to high tailwater.

Inlet control occurs when the culvert barrel is capable of conveying more discharge than the inlet will allow. The control section is located just inside the entrance of the culvert. The flow passes through critical depth at the control section and becomes supercritical downstream of the inlet.

Under inlet control, the culvert acts as an orifice or weir.

If the inlet is submerged, the flow condition resembles that of an orifice;

if the inlet is unsubmerged, the flow condition resembles that of a weir.

8.3 OUTLET CONTROL

|

|

Outlet control occurs under the following conditions:

When TW > 1.2 D, i.e., for high tailwater. In this case, the culvert barrel will be completely full of water, resembling closed-conduit flow. The headwater may be computed by applying the energy equation from the upstream (u/s) pool elevation to the downstream (d/s) pool elevation. The headwater is directly determined by the tailwater elevation and the frictional characteristics of the culvert barrel.

-

When inlet and outlet are submerged.

-

When the culvert slope is mild (subcritical flow) and both the headwater and tailwater are less than the culvert diameter (HW < D; TW < D). In this case, the best approach is to calculate the water-surface profile.

Figure 8-5 shows a schematic portrayal of flow rate as a function of headwater energy under inlet and outlet control (U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2014). Note that as the discharge increases from low to high, at a certain level the flow changes abruptly more or less from inlet control to outlet control.

|

8.4 CULVERT DESIGN

|

|

The following steps are followed in culvert design:

Assemble design data

Discharge,

Tailwater elevation, and

Slope of culvert barrel.

Choose the culvert characteristics

Cross-sectional shape (circular, square, rectangular, arch),

Dimensions (diameter, if circular),

Barrel length,

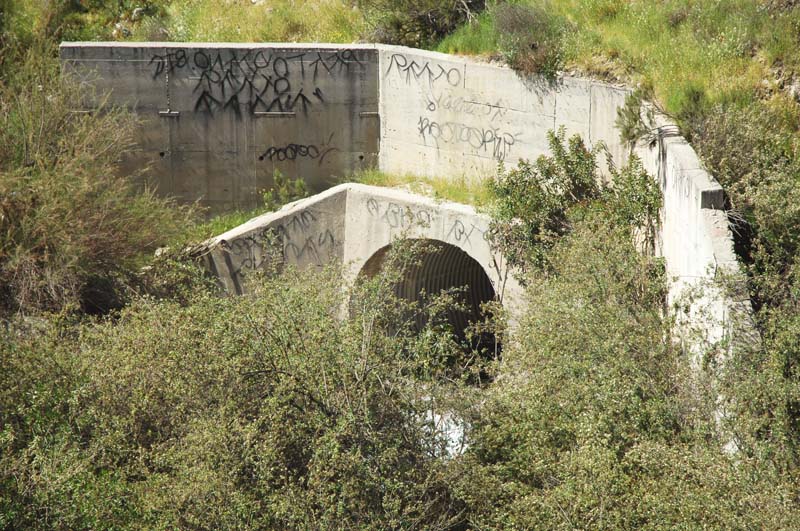

Kind of material (Figs. 8-6 and 8-7) (concrete, corrugated steel, corrugated aluminum, stone masonry), and

Type of entrance (square-edged or rounded).

Fig. 8-6 A set of two culverts made with corrugated steel.

Ascertain the prevailing type of control (inlet or outlet), based on (a) headwater elevation, (b) tailwater elevation, (c) diameter, and (d) slope.

If inlet control prevails, calculate the required headwater elevation to pass the design discharge.

If outlet control prevails, calculate the required headwater elevation using (a) the energy equation or (b) water-surface profile computations.

If the calculated headwater elevation is greater than allowed, choose a larger-size culvert and repeat the process.

In some cases, it may not be possible to determine the type of control a priori. In this case, both calculations are advised. The design type of control is that which results in the greatest headwater elevation.

Other design considerations in culvert design

Piping in the embankment surrounding the culvert,

Local scour at culvert outlet,

Erosion of fill material near the inlet,

Clogging with excessive debris, and

Provision for fish passage.

|

|

Design Example

Design a culvert for the following conditions:

Solution

|

QUESTIONS

|

|

What is a culvert?

What is the typical return period for culvert design?

When is a culvert under inlet control?

When is a culvert under outlet control?

List the hydraulic variables affecting culvert flow.

List other considerations in culvert design.

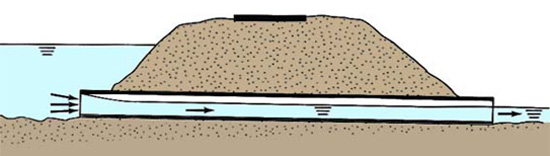

Fig. 8-10 The Arizona crossing, typical culvert used in the southwest.

PROBLEMS

|

|

Design a circular concrete culvert with the following data: Q = 300 cfs; inlet invert elevation z1 = 100 ft; tailwater depth y2 = 4 ft; barrel slope So = 0.02; barrel length L = 200 ft; Manning's n = 0.013; roadway shoulder elevation Es = 112 ft; upstream freeboard Fb = 2 ft. The entrance type is square edge with headwalls (Fig. 8-10). Use ONLINECHANNEL 06 to calculate normal depth and ONLINECHANNEL 07 to calculate critical depth in the culvert.

Fig. 8-11 Typical culvert underpass.

Design a circular concrete culvert with the following data: Q = 500 cfs; inlet invert elevation z1 = 100 ft; tailwater depth y2 = 4 ft; barrel slope So = 0.01; barrel length L = 200 ft; Manning's n = 0.013; roadway shoulder elevation Er = 115 ft; upstream freeboard Fb = 2 ft. The entrance type is square edge with headwalls. Use ONLINECHANNEL 06 to calculate normal depth and ONLINECHANNEL 07 to calculate critical depth in the culvert. Verify the culvert design using ONLINECULVERT.

REFERENCES

|

|

Chow, V. T. 1959. Open-channel Hydraulics. McGraw Hill, New York.

Ponce, V. M. 2008. Questions and answers on the return period to be used for design. Online article.

Roberson, J. A., J. J. Cassidy, and M. H. Chaudhry. 1998. Hydraulic Engineering, Second edition, Wiley.

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. 2014. HEC-RAS River Analysis System. Version 4.1, Hydrologic Engineering Center, Davis, California.

| http://openchannelhydraulics.sdsu.edu |

|

201025 20:30 |