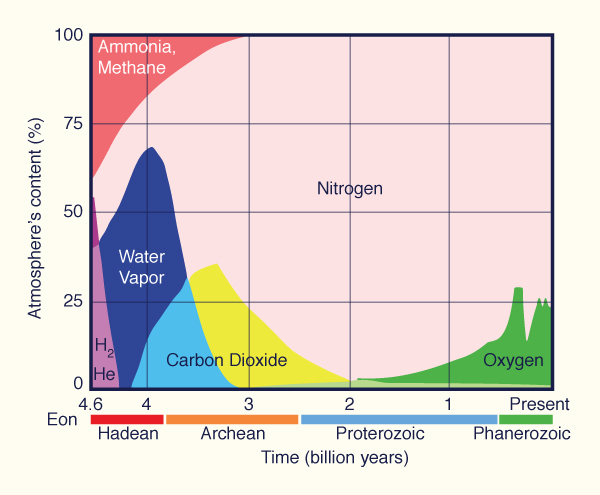

1. PHOTOSYNTHESIS AND RESPIRATION Photosynthesis began about 3 billion years ago; respiration began about 0.6 billion years ago.1 Photosynthesis is carried out by green plants, which take carbon dioxide from the air, incorporate it into organic matter, and release oxygen as a byproduct. Respiration is carried out by animals, which take oxygen from the air, use it to burn organic matter, and release carbon dioxide as a byproduct.

In Nature, there is a dynamic balance between photosynthesis and respiration. Too much photosynthesis reduces the amount of carbon dioxide in the air and leads to cooling of the lower atmosphere; conversely, too much respiration increases the amount of carbon dioxide in the air, leading to warming of the lower atmosphere.2 Figure 1 shows the composition of the Earth's atmosphere through geologic time. The current levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide are about 21% and 0.041%, respectively.

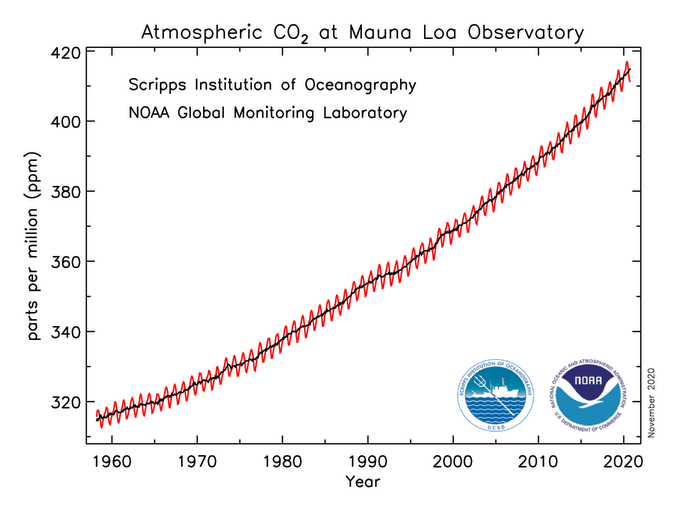

For the past 250 years, but more intently since the early 1900s, humans have been engaged in an experiment of global proportions by pursuing a type of development seemingly at odds with Nature. In effect, by producing artificial animals, humans have been increasing the amount of respiration, while at the same time decreasing the amount of photosynthesis by eliminating a significant number of plants through the paving of formerly productive land. The net effect is a double whammy, which is reflected in the sustained warming of the lower atmosphere over the past sixty years. To put it in numbers,

the concentration of carbon dioxide in the lower atmosphere has increased from 290 ppm at the turn of the 20th century to 415 ppm at the

present time (2021) (Fig. 2).

In the past 25 years alone, the concentration of carbon dioxide has increased at an average rate of

2. THE PROPORTIONS OF NATURE Photosynthesis and respiration are indeed opposite processes, and they both draw their inputs from the lower atmosphere. Therefore, the concentration of the inputs should roughly resemble the mass quantities in the terrestrial banks. In other words, the ratio of oxygen to carbon dioxide in the atmosphere should reflect the ratio of floral to faunal mass on the Earth's surface. Let's look at the first ratio, using the 1900 value for CO2:

The total floral biomass in the Earth is difficult to estimate precisely [Fig. 3 (a)]. The total live biomass is about 560,000,000,000 tons of carbon (C) (Wikipedia: Biomass). In terms of organic matter (CH2O), the amount is about 1,400,000,000,000 tons. The total dry faunal biomass, including humans, is estimated to be about 2,500,000,000 tons (Wikipedia: Biomass) [Fig. 3 (b)]. Therefore, the ratio of floral to faunal biomass is:

The proportionality between the two ratios is:

The dry biomass of humans is about 100,000,000 tons.

In terms of respiration, one automobile is equivalent to about three persons.3

Thus, we can add (3 × 100,000,000) = 300,000,000 tons to the natural faunal biomass (2,500,000,000) to get the equivalent total

faunal biomass of 2,800,000,000 tons.

At the present time (2019), the concentration of carbon dioxide has increased to 413 ppm

These calculations constitute only a start, because they do not consider the decrease in floral biomass from stage 1 (1900) to stage 2 (2019), or the additional increase in equivalent faunal biomass, since vehicles other than automobiles have not been included in stage 2. [Note that the calculations shown here are not intended to depict actual numbers; only general trends].

3. THE SOLUTION The solution is simple in theory but difficult in practice:

Yet, humans have been doing exactly the opposite for the past 120 years.

Transportation based on fossil fuels is regarded as the culprit, while the

paving of roads to facilitate transportation

exacerbates the problem Barring putting a halt to development, a feasible course appears to be carbon sequestration, i.e., extracting carbon from the atmosphere and depositing it somewhere out of sight. This would accomplish the same feat as humans had somehow developed a way of producing artificial plants. Yet technically and economically feasible carbon sequestration remains a long way from being a practical solution to this intensely human predicament.

REFERENCES

1 Cloud, P., and A. Gibor. 1970.

The oxygen cycle.

Scientific American, Vol. 223, No. 3, September, 111-123.

2

3

4 |

| 201203 |