|

1. INTRODUCTION

Across the landscape, plants get the water they need from various sources,

including surface and subsurface water.

Surface water occurs in the form of ponds, lakes, streams, and rivers.

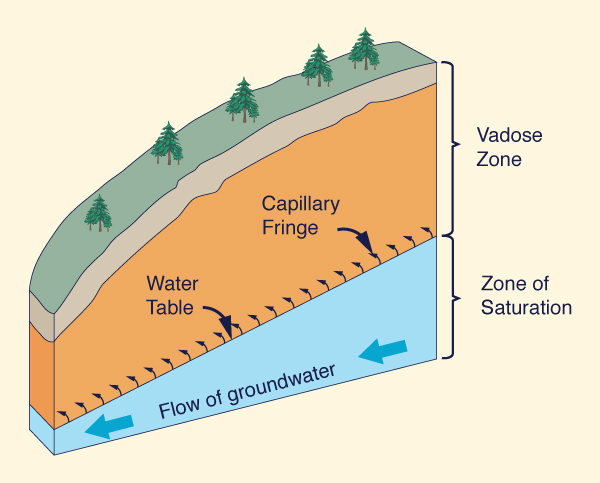

Subsurface water lies below the ground surface, first

in the unsaturated or vadose zone

and, secondly, below the water table, in the zone of saturation

At a given location, the source of water used by vegetation depends on the prevailing climate and the local geology and geomorphology. In arid climates, certain types of vegetation get their water exclusively from groundwater. Indeed, a host of desert plants are known to pump groundwater, which may lower the water table, albeit temporarily. Over the past century, developed human societies have learned to tap groundwater for various uses. Thus, the question arises: Are humans in competition with plants for the groundwater resource? Would excessive well pumping affect the health of vegetative ecosystems, particularly in arid regions where some plants are known to rely solely on groundwater? These are relevant questions, because the health of arid vegetative ecosystems is at stake. The latter provide a host of natural services, including carbon fixation, erosion control, wildlife habitat, contaminant filtering, low albedo, and scenic beauty.1 These services may be impaired by the excessive pumping of groundwater. 2. TYPES OF WATER

To understand where water comes from, how much of it is already committed by Nature,

and how much may be available for human use, we must take a close look

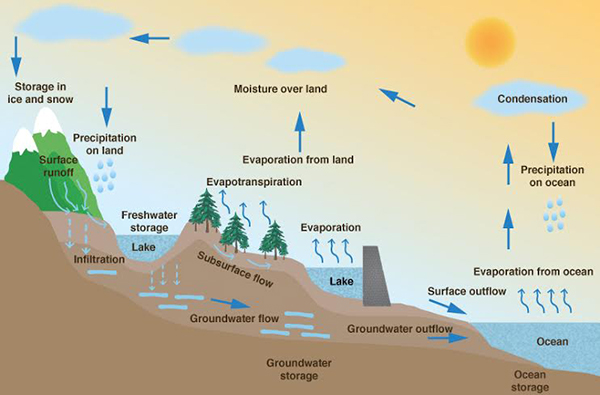

at the hydrologic cycle. Water originates in the oceans, evaporates into the atmosphere and moves inland,

eventually to precipitate

and convert into runoff, returning to the ocean to complete the cycle (Fig. 2).

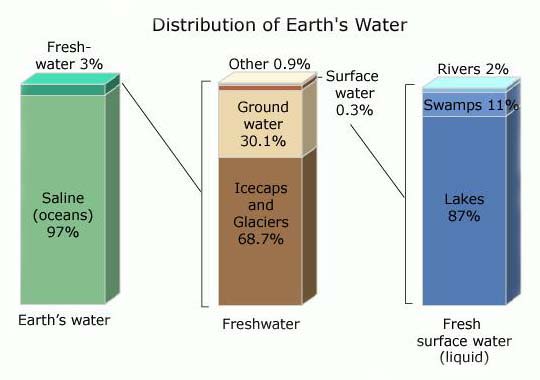

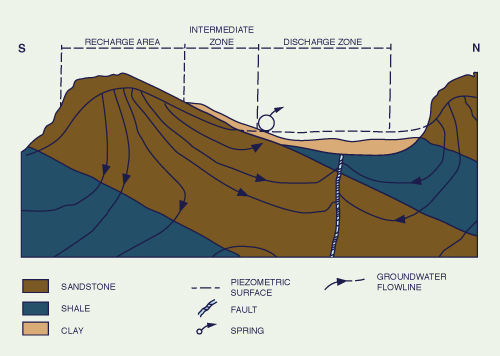

While on land, runoff separates into surface water and subsurface water. In turn, subsurface water is of two types: (1) unsaturated flow, and (2) saturated flow. Unsaturated subsurface flow lies within the vadose zone; saturated subsurface flow lies within the zone of saturation (Fig. 1). The thickness of the vadose zone depends primarily on the prevailing climate and, to a lesser extent, on the local geomorphology. In humid climates, the water table is generally close to the ground surface, while in arid climates it may lie at greatly varying depths. For instance, Meinzer (1927) has documented depths to the water table in the arid/semiarid western United States varying between 1 ft (0.3 m) and 62 ft (18.9 m). Significantly, Meinzer's data predates the intensive groundwater development that has taken place in the Western United States in the past 50 years. Groundwater differs from surface water in two important respects: Quantity and quality. Surface water runs off the ground readily to join adjacent streams and rivers, or else, it collects in natural depressions, where it becomes available for evaporation. In contrast, groundwater has been accumulating in the Earth's crust through geologic time, while slowly flowing toward the nearest ocean. Chebotarev (1955) has estimated the thickness of the water-bearing crust as the upper part of the lithosphere, consisting of the loose products of disintegration of igneous and metamorphic rocks, with a depth of approximately 10 miles (16 km). The U.S. Geological Survey has estimated the quantity of groundwater as more than one-hundred times that of surface water (Fig. 3). Thus, there is certainly a lot more groundwater than surface water. The advantage, however, appears to end there, because while surface water is generally fresh, the same does not follow for groundwater. The deeper the groundwater, the older it is and, consequently, the more saline it is likely to be (Ponce, 2012a). Also, while surface water flow is driven by gravity, groundwater pumping relies on imported energy; if the energy comes from burning fossil fuels, the carbon footprint increases.2

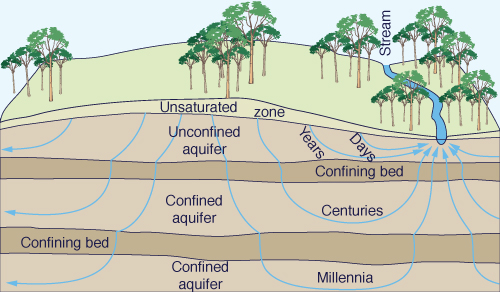

Age is perhaps the most significant difference between surface water and groundwater. On a global basis, surface water recycles every 9 to 16 days, with an average of 11 days (World Water Balance, 1978; L'vovich, 1979). Evaporation, evapotranspiration and surface runoff are the agents responsible for the relatively fast cycling of surface water. Thus, surface water is completely renewable in the short term. Unlike surface water, groundwater does not recycle readily. Rates of groundwater turnover vary from days to years, and from centuries to millennia, depending on aquifer location, type, depth, properties, and connectivity. The average time for the renewal of groundwater is 1,400 years (World Water Balance, 1978). Shorter renewal times tend to be associated with shallow groundwater, while longer renewal times are associated with deep groundwater (Fig. 4). Significantly, renewal rates of deep groundwater are about 1/15 of those of shallow groundwater (Jones, 1997). Yet some fossil, or paleogroundwaters may have ages exceeding 30,000 years. Old groundwaters are practically nonrenewable; once used, they are not likely to recharge any time soon.

Thus, while surface water is entirely renewable, groundwater is not. The use of surface water is sustainable, while the use of groundwater may not be. Sustainability implies renewability; lack of renewability is deemed to be unsustainable.

3. WATER NEEDS OF VEGETATION

All vegetative ecosystems satisfy their need for water

by drawing either surface or subsurface water.

Some may rely on surface water, some others on vadose-zone water, and yet some others

on groundwater. The mix generally depends of type of species,

climate, soils, geology, and geomorphology.

In humid regions, where the water table is close to the ground surface,

plants may get their water from all sources; however, in arid regions, where

surface water is scant,

only plants that can successfully tap the groundwater may be able to survive

the recurrent droughts.

The phreatyphytes, or well plants,

can send their roots deep down, enough to reach the water table (Meinzer, 1927).

Other plants draw their water from the vadose zone.

Thus, the depth of the vadose zone has a direct

bearing on the survival of different types of plant species.

In humid regions, the depth of the vadose zone is small and many species are able to

tap the groundwater.

In arid regions, the depth of the vadose zone may be large enough to

enable only a few species to reach the water table. To conclude:

In humid regions,

vegetative ecosystems are supported by surface and subsurface water, including groundwater,

which lies at relatively shallow depths. In these regions,

precipitation is plentiful, groundwater is abundant, and replenishment is fast.

In arid regions,

vegetative ecoystems are often supported by groundwater.

In these regions, precipitation is scant, groundwater is meager, and replenishment is slow.

How does groundwater pumping affect arid

vegetative ecosystems? The answer to this question

requires a thorough grounding in

concepts of geology, geomorphology, hydrology, and ecology. In the following sections

we endeavor to examine these fields in search for effective ways of resolving the competition

between well plants and pumping wells.

4. GEOLOGY

Geology is the source of everything natural.

Local geology interacts with the prevailing climate to condition the geomorphology.

Geologic uplift is responsible for mountain building;

in turn, mountains are eroded by the action of rain and gravity. The products of erosion

are transported by runoff, eventually to settle in and fill the downstream valleys.

The Earth's crust is generally not completely solid,

featuring fractures, cracks, and other discontinuities, where water tends to accumulate.

These fractures are due to tectonic processes and freeze/thaw cycles.

Moreover, the valley soils have a granular structure,

with voids taking up a sizable fraction of the total volume.

Thus, the Earth's surface crust collects

water:

The accumulation of water below the ground surface, in aquifers,

has been occurring

through geologic time.

Aquifers are of two types: (1) fractured rock, and (2) alluvial.

Fractured-rock aquifers are associated with mountains and

uplands, where rain is abundant and there is an active groundwater recharge.

Alluvial aquifers are present in the soil-filled valleys and lowlands,

where groundwater discharge generally takes place

Fractured-rock aquifers differ from alluvial aquifers in three important respects:

The relative storage volume is measured by the storage coefficient, i.e., the ratio of voids volume to total volume. Alluvial aquifers have comparatively large storage coefficients, generally varying in the range 0.01 - 0.30 (Freeze and Cherry, 1979). In contrast, fractured-rock aquifers have much smaller values, typically in the range 0.0001 - 0.01. The rate of recharge and discharge of an aquifer is a measure of the speed at which it replenishes following recharge, and depletes following discharge. The timing response of fractured-rock aquifers may be measured in days and months, while that of alluvial aquifers may be measured in years and decades. This is because the flow of water within a rock aquifer is advective, through the fractures, typically in a two-dimensional mode, at relatively high speeds (Fig. 6).3 On the other hand, the flow of water within an alluvial aquifer is diffusive, through the porous media, occurring at much slower speeds than those that could be attained by pure advection (Ponce, 2006).4

Fractured-rock and alluvial aquifers differ in the predominant mode of exfiltration. Fractured-rock aquifers feature springs wherever fractures and the water table intersect at or near the ground surface (Fig. 7). Springs are related to the number, size, and connectivity of fractures; therefore, they reflect the local geology and tectonic activity. On the other hand, the exfiltration of alluvial aquifers is driven by the local geomorphology, as characterized by stream bottoms, surface depressions, grabens, and so on.5 Fractured-rock aquifers exfiltrate through springs; alluvial aquifers exfiltrate through the baseflow [the dry-weather flow] of streams and rivers.

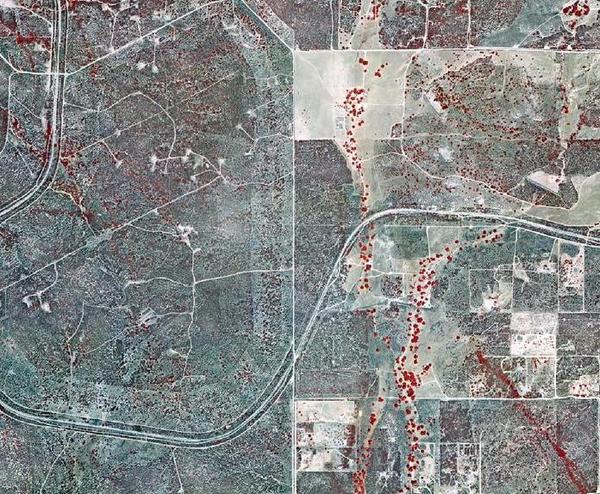

The foregoing facts have a significant bearing upon the relation between groundwater and vegetation. Above a fractured-rock aquifer, plants will colonize the immediate vicinity of springs, which, for the most part, are randomly distributed. This "upland interaction" between plants and groundwater takes place ostensibly in the absence of a clearly defined stream channel. Conversely, in an alluvial aquifer, plants are known to colonize the immediate vicinity of streams, where the groundwater is shallowest. This "riparian interaction" takes place between plants and groundwater in the presence of a stream channel. Figure 8 shows a typical example of upland vs riparian interaction between groundwater and vegetation. This infrared image depicts a portion of Tierra del Sol, in eastern San Diego County, California. Two branches of Tierra del Sol Creek are shown, featuring a riparian community of coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) [shown in red color], sparsely populated along the two ephemeral stream channels. Also shown (on the bottom right) is a tightly packed upland linear forest of red shank (Adenostoma sparsifolium), which is fed by water exfiltrating through a fracture in the underlying rock (Ponce, 2006).

5. GEOMORPHOLOGY

If geology may be considered the father of ecosystems,

geomorphology can be taken as the mother.

The analogy is quite fitting, because while geology contributes the required nutrients,

geomorphology helps in the nourishment by facilitating access to a permanent source of water [groundwater].

Climate determines the average depth to the water table;

geomorphology determines the actual depth. In humid regions, the water table

lies close to the surface, while in arid regions it lies at greater and varying depths.

In Nature, geology, geomorphology, hydrology, and ecology are thoroughly intertwined into

a complex web

of relations whose sole purpose is to sustain the vegetative ecosystems.

Significantly, geomorphology stands out as the

glue that effectively ties all the other components together.

The role of geomorphology is nowhere more

marked than in arid regions, where it determines whether a plant or ecosystem will exist or not.

An example or such determinacy is an oasis, a depression where the groundwater

comes close enough to the surface to be within reach of the vegetation

In certain places, depending on the local geology and geomorphology, exfiltration may be of such magnitude as to feed small lakes embedded in otherwise desertic landscapes. For instance, Fig. 10 shows the Huacachina Lagoon, an oasis near Ica, Peru. Groundwater exfiltrates into this natural depression, located within Peru's coastal desert.

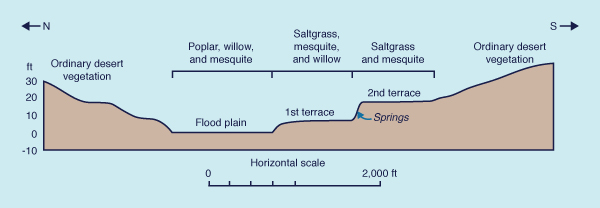

Meinzer (1927) has aptly described the relation between geomorphology, groundwater, and vegetation, focusing specifically on the arid lands of the western United States. He states:

Figure 11 shows the vegetational gradient along a cross section of the Mojave river valley at Camp Cady, California (Meinzer, 1927). It is seen that different species occupy different levels in the profile. The dimensions of the terraces depend on the proximity to groundwater, which is conditioned by the local topography, i.e., by the geomorphology.

Vegetational gradients of the type shown in Fig. 11 are not restricted to the arid landscapes described by Meinzer (op. cit.). Figure 12 shows the sequence of cerrado-campo-gallery forest which recurs in the subhumid, highly dissected savannah woodlands of Mato Grosso, in central western Brazil. The cerrado (dense scrub forest) occupies the higher ground, out of reach of the groundwater. The campo (grassland) occupies the middle ground, subject to occasional flooding. The gallery forest occupies the lower ground, where there is a significant and active interaction with groundwater (Ponce and Cunha, 1993).

In summary, geomorphology helps explain the presence of different types of vegetation across a dissected landscape. In particular, in arid regions the depth of the vadose zone and, consequently, the proximity to the water table, are conditioned by local geomorphology. Thus, geology and geomorphology are the primary agents determining which ecosystems are able to survive and thrive, and where. Soil texture, which affects the thickness (depth) of the capillary fringe, acts as a secondary factor. 6. HYDROLOGY

Hydrology

encompasses all the waters of the Earth, including those that flow on the surface and below the surface.

Surface water and groundwater have quite distinct physical and chemical properties;

however, the differences appear to end there, because one can convert into the other, and vice versa.

Infiltration is the means by which surface water becomes groundwater;

conversely,

exfiltration is the means by which groundwater becomes surface water.

In arid climates,

surface water infiltrates into the groundwater as it flows over ephemeral streams

Streams with characteristics in between those of ephemeral and perennial are referred to as intermittent (Fig. 14). These streams may have baseflow only during the wet [or rainy] season.

Surface runoff consists of direct and indirect runoff. Direct runoff flows on the surface; indirect runoff flows below the surface. Direct runoff converts to flood flows, while indirect runoff winds up as baseflow. Thus, flood flows and baseflow are seen to be mutually exclusive. The hydrologic peak-to-low flow ratio helps quantify the role of groundwater. Generally, the larger the stream, the lower the peak-to-low flow ratio. For example, Fig. 15 shows the Amazon river, the largest in the world. The peak-to-low flow ratio ranges between 2 and 3, the lowest in the world. In contrast, much smaller streams may have quite large peak-to-low flow ratios, depending on the local geology, geomorphology, and soils. For instance, the Pirai river, in Santa Cruz, Bolivia, may reach peak-to-low flow ratios exceeding 1000 for a few days during the wet season (January to March) (Fig. 16).

The relative quantities of surface and subsurface runoff affect the relation between groundwater and vegetation. When the ratio of surface runoff to total runoff is large, most of the water is flowing on the surface. Conversely, when the ratio of surface runoff to total runoff is small, most of the water is flowing below the surface, as baseflow. Large quantities of baseflow are made possible by a shallow water table. In turn, this leads to a substantial interaction between vegetation and groundwater. In this case, plants are not limited by lack of water, being able to use all types of water, including surface water, vadose water, and groundwater proper. A total absence of baseflow implies a water table below the stream bottom, sometimes at a great depth. In this case, plants do not use surface water; instead, they send their roots, often to great depths, to tap the underlying groundwater (Fig. 17). These are the phreatophytes documented by Meinzer (1927).

In summary, local climate, geology, geomorphology, and hydrology interact

to either foster or discourage the development of vegetation.

In particular, in semiarid and arid regions, more often than not, the presence of phreatophytes

is an indication of the proximity of groundwater.

In these cases, the depth to the water

table may vary from a few feet to as much as 50 to 60 feet (Meinzer, 1927)

7. ECOLOGY

Ecology deals with the interactions between organisms and their environment.

An ecosystem, the basic unit of ecology,

consists of living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) components.

Living components are the plants, animals, and microbes.

Non-living components include the surrounding air, water, nutrients, soil and rock.

Solar energy enters ecosystems through the process of photosynthesis, by which

green plants take carbon dioxide from the air and water from the surrounding environment to manufacture organic matter

in the presence of light. The reaction releases oxygen as a byproduct, which enters the atmosphere. Through respiration, which is

the exact biochemical opposite of photosynthesis, animals obtain the energy necessary for their livelihood by burning organic matter (food) using

oxygen from the air (for combustion) and releasing carbon dioxide as a byproduct.

The atmosphere acts as the reservoir which provides both the carbon dioxide for the plants

and the oxygen for the animals.

Depending on the local climate, geology and geomorphology,

plants and animals organize themselves in

distinct communities, where various species may coexist.

A plant community is a collection or association of

plant species within a designated geographical unit or habitat,

which forms a relatively uniform patch, distinct from other patches; see, for instance,

the two distinct habitats shown in

Fig. 19: (a) An arid desert, which is crossed by a perennial stream,

and (b) a humid tropical montane forest (Ponce, 1995).

A plant community may be described either floristically (the plant species) or physiognomically (the plant's appearance). The floristic description refers to the various vegetative species present in the community. The physiognomic description focuses on the physical structure of the community, its characteristic height, canopy density, and specimen size (trunk diameter at breast height). Plants require inputs of solar energy, carbon dioxide, water, and nutrients. Solar energy varies primarily with latitude; plants in tropical and temperate regions are able to get their energy needs during the day or, significantly, during the growing season. Carbon dioxide exists in the air in concentrations that are sufficient for plants to avail themselves of as much carbon and oxygen as needed (Bolin, 1970). Therefore, the limiting factors are water and nutrients (Ponce, 2008).

8. HYDROECOLOGY

Hydroecology deals with the relations between plants and water.

In Nature, water and nutrients are tied together.

Water serves as the means to carry the nutrients to the plant.

Without nutrients, the construction of the biosphere would come to a halt;

without water, photosynthesis and biomass production could not take place.

Field observation indicates

that the amount of biomass is directly related to the amount of environmental moisture;

compare for instance, the driest and wettest spots on Earth shown in Fig. 20.

The Atacama desert, in northern Chile, with near zero precipitation, is the driest spot;

Cherrapunji, in Meghalaya, India, with close to 12,000 mm of mean annual precipitation, is the wettest

spot.

The tallest [and oldest] trees on Earth are the California (coastal) redwoods (Sequoia sempervirens) (Fig. 21). The coastal redwood is a long-lived evergreen tree, living 1,200-1,800 years or more. The species includes the tallest trees of record, measuring up to 379 ft (115.5 m) in height and up to 26 ft (7.9 m) in diameter at breast height. Its natural habitat is coastal northern California, particularly in Humboldt and Del Norte counties, where mean annual precipitation reaches 125 in (3,175 mm), the largest in California. Its natural habitat extends to the adjoining southern coast of Oregon.

The coastal redwoods usually grow in the mountains, where precipitation from the incoming ocean moisture is maximized. The tallest and oldest trees are found in deep valleys and gullies, where there are year-round streams and fog drip is regular.6 Trees located above the fog layer, above about 2,300 ft (700 m), are shorter and smaller due to the drier, windier, and colder conditions. The widest tree in the world is a Montezuma cypress (Taxodium mucronatum) located in Santa Maria del Tule, about 6 mi (9 km) east of the city of Oaxaca, Mexico [Fig. 22 (a)]. In 2005, its trunk had a circumference of 137.8 ft (42 m), which represents a diameter of 43.9 ft (13.4 m). The best estimate for the age of this tree, based on growth rates, is 1,433 to 1,600 years.

The tree is located near the center of a narrow valley

between two hills, within the confines of the

broader valley of Oaxaca [the precise location is labeled A in Fig. 22 (b)].

The mean annual precipitation in the area averages 746 mm (29.4 in), a bit less than the

global average

All vegetation

responds readily to moisture inputs from all sources, including surface, soil, groundwater, and air.

Absence of water is definitely limiting; on the other hand,

ample water leads to trees of great size such as the

California redwoods (Fig. 21). Too much water may lead to

a dearth of nutrients, due to soil leaching through geologic time.

However, large tropical forests such as the Amazon

are able to store nutrients in their extensive

canopy and recycle them as appropriate

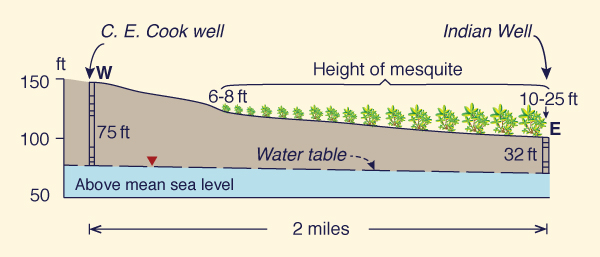

The preceeding examples have shown conclusively that the presence of water has a direct bearing on the physiognomy (height and density) of vegetation. This fact is nowhere clearer than in a desert landscape, where the size differences may be attributed to the prevailing gradient in the depth to the water table. For instance, Brown (1923) has documented the height of mesquite (Prosopis sp.) between two wells located in the Coachella valley, near the Salton Sea, California (Fig. 24). Mesquite grows as a dense forest 10 to 25 ft high along the eastern well, and of somewhat less size (6 to 8 ft) on high sand dunes to the west. Within a distance of 2 miles, from east to west, the depth to the water table increases from 32 ft to 75 ft. Ostensibly, mesquite does not grow beyond a depth to the water table of 50 ft.

In fractured-rock aquifers, the influence of moisture availability on the height and density of vegetative ecosytems is confirmed by the existence of linear forests (lineaments).7 Figure 25 shows a remarkable linear forest of tall red shank (Adenostoma sparsifolium) in Tierra del Sol, San Diego County, California. This forest is fed by water exfiltrating through a linear fracture in the underlying rock (Ponce, 2006).

Two closely related chaparral species, chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum) and red shank (Adenostoma sparsifolium) are significantly represented in Tierra del Sol. Although congeners, these two species are not at all alike in appearance. Stands of chamise chaparral are dull, dark-green in color and uniform in appearance. The mature chamise plant is a medium-sized shrub 2 to 8 feet tall, with sparse leaf litter. In contrast, red shank is a tall, round-topped arborescent plant 6 to 18 feet high, with thick, naked stems and considerable leaf litter, 0.5 to 2 inches in depth. Red shank appears to dominate over chamise on sites with higher moisture content, organic matter, and nutrient availability (Beatty, 1984). Despite being sclerophyllous, red shank can be shown to violate several definitions of sclerophyllous plants. First, red shank remains physiologically active during summer drought; thus, it is drought tolerant without being drought dormant (Hanes, 1965). Secondly, its root morphology is unique among the chaparral. Its shallow root system suggests that its moisture for summer growth must come from the top layers of the substrate. Red shank seems to be a type of shrub well adapted to drought conditions, but lacking the obvious morphological characteristics suggesting such adaptability (Shreve, 1934). Thus, the water affinities of red shank lie in between those of the xerophytes, which are well adapted to drought, and those of the mesophytes, which habitually require a more sustained moisture source. In semiarid regions, this ecological niche must be connected to the presence of groundwater or, at the very least, to plenty of vadose moisture, which suggests a close proximity to groundwater. The linear forests of fractured-rock aquifers are similar to the oasis in that both exfiltrate groundwater. The linear forests are indeed the loci of groundwater exfiltration through the fractures. This confirms the importance of geology in a rock aquifer, in contrast to geomorphology in an alluvial aquifer. Another example of the connection between geologic features, groundwater, and vegetation in an upland environment is the lone specimen of coast live oak (Quercus agrifolia) shown in Fig. 26 (a). This large tree sits next to a spring (note the dark spot in the foreground, and the bathtub!) located at the [western] downstream edge of the large dike shown in Fig. 26 (b) (Ponce, 2006).

9. HYDROGEOLOGY

Hydrogeology deals with the distribution

and movement of groundwater in the soil and rocks of the Earth's crust.

The main objective is to determine

the amount of groundwater that is possible to extract from an aquifer, by pumping,

without causing undesirable or unacceptable consequences.

The benefits of groundwater are direct and measurable, encompassing

the use of water for diverse purposes, among them, notably, irrigation

and domestic/industrial

water supply. The costs of groundwater utilization include:

The energy expenditure

required to lift the water literally off the ground,

The cost of well drilling and maintenance,

particularly the cost of drilling deeper wells as a result of groundwater depletion, and

Other environmental and socioeconomic

costs, which are much harder to quantify.

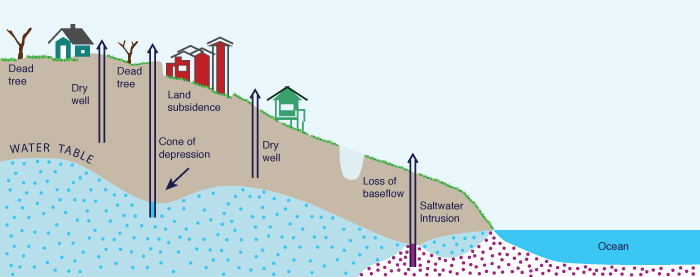

Among these other costs (or impacts) are (Fig. 27):

Water table depletion, progressibly

making it harder for all users of the aquifer to pump groundwater.

Loss of wetlands,

including possible impairment of oasis, phreatophytic, and spring-fed vegetation.

Loss of baseflow and riparian corridors, which may

trigger

changes in channel morphology and lead to streambank erosion and increased sediment loads.

Land subsidence; for instance, see the Las Vegas experience

(Fig. 28)

(Galloway et al., 2013).

Salt-water intrusion in coastal environments.

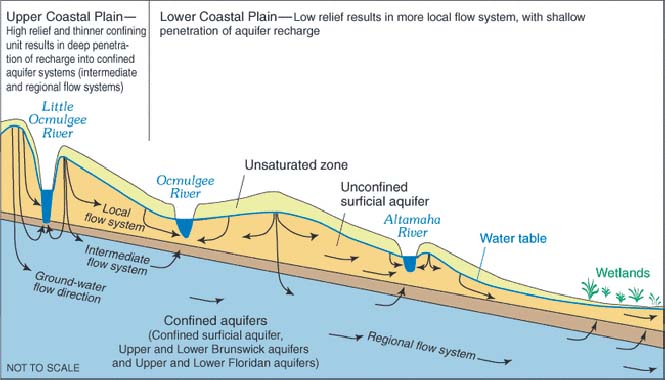

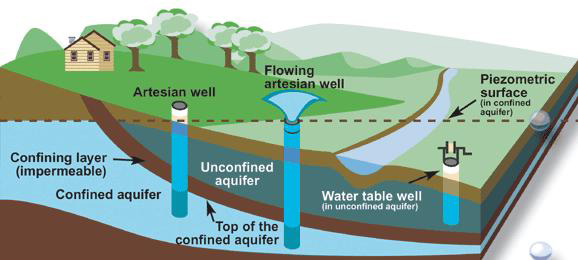

A groundwater flow system may consist of one or more aquifers of different types. The aerial extent of groundwater flow systems varies from a few square miles or less to tens of thousands of square miles. The length of groundwater flow paths ranges from a few feet to tens, and sometimes hundreds, of miles. A deep groundwater flow system with long flow paths between areas of recharge and discharge may be overlain by, and in hydraulic connection with, several shallow, more localized, flow systems. Thus, the definition of a groundwater flow system is to some extent subjective and depends in part on the scale of the study (Alley et al., 1999). Aquifers may be of two types: (1) unconfined, and (2) confined. Unconfined aquifers lie near the surface and, for the most part, constitute shallow groundwater. Confined aquifers lie at greater depths, below a confining layer and often under pressure. Confined aquifers may constitute either shallow or deep groundwater, depending on the characteristics of the regional groundwater flow system (Fig. 29).

Depending on their geologic age, aquifers may be tertiary or quaternary. Tertiary aquifers can lie near the surface or at greater depths, and can be confined or unconfined. They are composed of rock, either igneous or sedimentary. Depending on their depth and connectivity, tertiary aquifers may contain either shallow or deep groundwater, or both. Quaternary aquifers lie within alluvial, glacial, or lacustrine deposits. They consist primarily of unconsolidated materials such as sand and gravel, but may also have some silt and clay. These aquifers are usually surficial (superficial); they flow through soils deposited throughout the Quaternary Period.8 These aquifers are either unconfined or confined, and contain, for the most part, shallow groundwater. Wells are three types: (1) water table well, (2) artesian well, and (3) flowing artesian well (Fig. 30). In a water table well, the water table is at atmospheric pressure; in an artesian well, the water pressure is greater than atmospheric; in a flowing artesian well, the water pressure is such that it can flow freely above the ground surface.

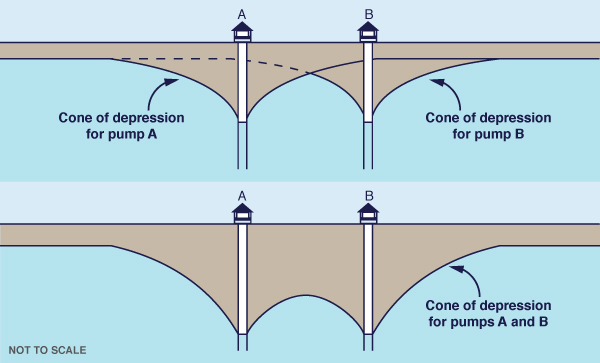

Pumping from a water table well lowers the groundwater levels near the well. The affected zone is known as the cone of depression, and the land surface above it, its area of influence. Well pumping changes the natural direction and amount of groundwater flow within the area of influence. If two cones of depression overlap, the interference reduces the water available to each well (Fig. 31). Well interference can be a problem when many wells are competing for the water of the same aquifer, particularly at the same depth.

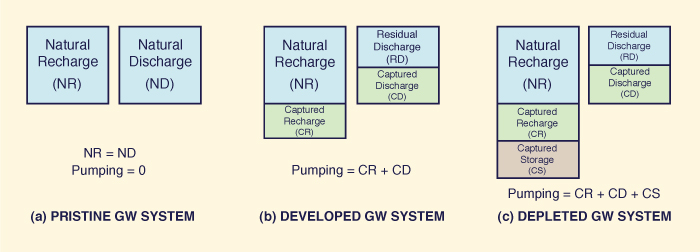

In cases where the area of influence of a well extends to a nearby stream or lake, there is a reversal in the flow direction and the water body begins to lose water to the well by induced recharge. Streams, wetlands, and lakes can dry up completely under sustained conditions of induced recharge. The crux of classical hydrogeology is the determination of the recharge, i.e., the amount of water that enters the control volume within a certain period of time.9 This recharge amount, interpreted as the safe yield of the aquifer, is the volume of water that could be available for pumping. This simplistic approach has been widely discredited because it assumes that groundwater is a volume, when in fact it is a flow (Ponce, 2007). In a pristine groundwater system, gross recharge equals gross discharge; therefore, net recharge is zero (Theis, 1940).10 Taking out [capturing] all the water that enters the control volume effectively means taking out most, if not all, the water that exits the control volume. Thus, downstream uses stand to be impaired. The latter includes wetlands, the baseflow of streams and rivers, and established riparian water rights, to name a few (Sophocleous, 2000). Over the past two decades, the concept of safe yield has been superseded by that of sustainable yield (Alley et al., 1999). The latter seeks to strike a compromise between safe yield, which purportedly uses all the recharge, and zero yield, which conserves all the groundwater. Sustainable socioeconomic yield allows the pumping of groundwater, but only up to a limit. Significantly, this limit is imposed, not based on hydrogeologic analysis, but rather on environmental and socioeconomic considerations (Ponce, 2007). The overall objective is to determine the percentage of recharge that may be pumped at a given location, without significantly affecting local stakeholders. The latter include the wetlands, baseflow, and those individuals or entities affected by the loss of riparian rights, land subsidence and/or salt-water intrusion. The aim is to limit/regulate the lowering of the water table, to which all the other factors are related. The determination of sustainable socioeconomic yield is a relatively new endeavor. The problem is complex, spanning across a gamut of established disciplines; therefore, it is best suited to adaptive management (Maimone, 2004; Seward et al., 2006). A value of sustainable socioeconomic yield amounting to a fraction of [gross] recharge is deemed appropriate, even though there is no physical relation between them. A value of 10% may be considered to be reasonably conservative, while somewhat higher values may represent a compromise (Ponce, 2007).11 What is patently clear is that any amount of pumping, if not put back into the aquifer, is a capture, and this capture has a net effect on the water table. To illustrate, Fig. 32 shows three stages in the development of groundwater systems:

Developed and depleted groundwater systems [Fig. 32 (b) and (c), respectively] generally result in a lowering of the water table. The greater the amount of capture, the greater the amount of depletion. Thus, sustainable groundwater systems aim to make sure that the lowering of the water table does not cause undesirable or unacceptable consequences (Alley et al., 1999). In practice, this requirement effectively limits groundwater pumping to a small percentage of the [gross] recharge (Ponce, 2012b).

10. PLANTS AND WELLS

It is clear that both plants and wells pump groundwater; this fact has been amply confirmed by theory and experience.

The two systems, one natural (plants)

and the other anthropogenic (wells), when located in close proximity of each other,

are actually drawing water from the same reservoir (Fig. 33). Therefore, the question arises:

Are wells in competition with the plants for the groundwater resource? If well pumping results in a lowering of the

water table within reach of the roots, the answer is an unequivocal Yes.

Every groundwater pumping project has an impact; actually, a collection of impacts, as shown in

Capture is defined as the amount of groundwater that is removed through pumping and not returned or put back into the aquifer. Capture that results in substantial water table lowering (depletion) has a host of negative effects, or impacts. The spatial and temporal reach of these impacts varies with the affected system and the amount of capture [See box below].

In conclusion, plants and wells are seen to be in competition for the groundwater resource, particularly in semiarid and arid regions, where groundwater may be the only source of water for most plants. Phreatophytes are counting on the groundwater for their livelihood, and if the groundwater table is lowered beyond their reach by anthropogenic action, they will eventually die and, therefore, cease to provide a host of natural services. Both riparian and upland ecosystems are likely to be negatively impacted by groundwater pumping. Riparian ecosystems are typically longitudinal, along the stream, and tap the water table in the dissected-and-filled alluvial landscape. On the other hand, upland ecosystems, particularly in mountainous regions, are more likely to be randomly distributed and to follow the fractures and springs (Fig. 34). In semiarid/arid landscapes, the situation may be more acute because of the limited number of springs.

Lowering of the water table as a result of pumping will encroach upon the livelihood of many desert vegetative species. The mesophytes will be particularly affected, since these typically require substantial amounts of water.12 The latter flows in springs and under depressions, following paths established by local geology and geomorphology.

11. ANALYSIS

The preceding sections have presented

clear evidence of the competition between groundwater use

and vegetative ecosytems. Climate, geology, and geomorphology have conditioned the type and extent

of vegetation throughout geologic time. On the other hand, intensive groundwater use,

made possible by mechanical pumping, has occurred only in the past 100 years or so.

In order to reconcile the

apparent competition, the following questions are posed:

Who uses groundwater?

What are plants useful for?

Where is the competition

between plants and wells most critical?

Could a middle ground be found that uses groundwater

without encroaching upon ecosystem health?

♦ Who uses groundwater?

Around the world, users of groundwater face the following realities:

There is not enough surface water to satisfy all the perceived needs or uses.

Local groundwater is less expensive

than imported surface water.

The available surface water may have been all

appropriated; thus, there is no other recourse but to tap

the local groundwater.

It is recognized that all groundwater of economic use

is in transit to the surface waters; thus, the existence of groundwater as an additional resource is subject

to interpretation. In many instances, groundwater is seen to be cheaper than surface water,

but when all environmental costs are considered, the difference in cost may be reduced and possibly even

reversed. While surface water is completely renewable, the same statement does not follow for groundwater.

Therefore, usage of groundwater must be done with caution, anticipating and mitigating

the impacts that this usage may have on local stakeholders, both natural and anthropogenic.

♦ What are plants useful for?

Plants provide a host of natural services, many of which still remain to be quantified in conventional

economic terms.

First and foremost, all green plants sequester carbon dioxide, thus helping to control the climate.

Thus, a permanent reduction in plant biomass has exactly the same effect as burning an

additional amount of fossil fuels.

In addition to carbon fixation and oxygen production, plants provide several other natural services,

including erosion control, habitat for wildlife, filtering of contaminants, low albedo (which encourages rain),

and scenic beauty, all of which have an intrinsic value.

Thus, the impairment of ecosystem health by excessive groundwater pumping could

have far-reaching consequences, that encompass aspects of climatology, biology, sedimentology,

and public recreation.

♦ Where is the competition

between plants and wells most critical?

The competition between plants and wells is most critical

in arid/semiarid environments, where many plants rely almost exclusively on groundwater.

Thus, pumping in a desert environment is most crucial,

not only because of the dependence of the vegetation on the groundwater resource,

but also because replenishment is likely to be slow, with recharge events

few and far between.

A conundrum is noted here: Groundwater pumping may not be as crucial in a humid environment, because in this case

surface water may be plentiful, largely eliminating the need for pumping.

♦ Could a middle ground be found that uses groundwater

without encroaching upon ecosystem health?

A middle ground may be found in the relatively new concept of sustainable yield.

The amount of groundwater capture should not be based on the outdated hydrogeologic principle

of safe yield. Instead, the allowable capture must be that which

can be maintained [for an indefinite time] without causing unacceptable

environmental, economic, or social consequences

(Alley et al., 1999). These consequences would have to be carefully evaluated

and accounted for in the economic analysis before the planned groundwater development takes place.

The latter requirement calls for renewed

interdisciplinary synthesis in groundwater resource

evaluation, to include ecology, surface-water hydrology, and the economics of natural resources.

12. CONCLUSIONS

The following conclusions are derived from this study:

Climate, geology,

geomorphology, and hydrology interact to foster or discourage the development of vegetation.

Many plants in arid/semiarid regions rely almost exclusively on

groundwater to satisfy their basic need for water.

The presence/absence of water has a direct bearing on the

height, width, and type and density of vegetation.

The concept of safe yield

of groundwater has been widely discredited because it assumes that groundwater is a volume, when in fact it is a flow.

In a pristine groundwater system, gross recharge equals gross discharge; therefore, net recharge is zero.

Plants and wells are in competition for the

groundwater resource; this competition

is most critical in the arid/semiarid environment, where many plants are seen to rely almost exclusively on groundwater.

Developed shallow groundwater systems

generally result in a lowering of the water table;

the greater the amount of groundwater capture, the greater the amount of lowering.

All groundwater of economic use is

in transit to the surface waters and may have already been committed;

thus, the existence of groundwater as an additional resource is not always to be taken for granted.

Riparian ecosystems (i.e., the gallery forests)

are typically longitudinal,

tapping the water table in the dissected-and-filled alluvial landscape.

Upland ecosystems (for instance, the lineaments) are more likely to

be randomly distributed in space

and to follow fractures, springs, and/or other geologic features.

Capture that results in a substantial lowering of the water

table has a host of negative impacts, of which the most important is a [more or less] permanent reduction in plant biomass.

A permanent reduction in plant biomass has exactly the same effect as burning an

additional amount of fossil fuels, thereby increasing the

carbon footprint.

Usage of groundwater must be exercised with caution, anticipating the impacts that

this usage may have on local stakeholders, both natural and anthropogenic.

The allowable groundwater

capture must be that which can be maintained [for a reasonably long time] without

causing unacceptable environmental, ecological, economic, or social consequences.

There is an urgent need for renewed interdisciplinary

synthesis in groundwater resource evaluation,

to include ecology, surface-water hydrology, and the economics of natural resources.

The effect of groundwater pumping on the health of arid vegetative ecosystems is examined herein.

Vegetative ecosystems are supported by a complex interaction of climate, geology,

geomorphology, and hydrology. In arid/semiarid regions, many plants rely almost exclusively on groundwater

to satisfy their basic needs for water. Globally, it is observed that the presence/absence of

water has a direct bearing on the height, width, and type and density

of vegetation.

It is seen that plants and wells are in competition for the groundwater resource. The competition is most critical

in arid/semiarid regions, where surface water is scarce and groundwater is the only recourse.

Developed shallow groundwater systems generally result in the lowering of the water table,

wherein the greater the capture, the greater the lowering.

Lowering of the water table stresses the plants that customarily rely on the groundwater.

In extreme cases, plants may die and springs and wetlands may disappear.

Groundwater capture that results in a substantial lowering of the water

table has a host of negative impacts, notably among them an increase in the carbon footprint.

Pumping of groundwater must be performed with caution, anticipating the impacts that

this pumping may have on local stakeholders, both natural and anthropogenic.

The allowable

capture must be that which can be maintained without

causing unacceptable environmental, ecological, economic, or social consequences.

There is an urgent need for interdisciplinary

synthesis in groundwater resource evaluation,

to include ecology, surface-water hydrology, and the economics of natural resources.

ENDNOTES

1

2

3 Advection is a transport of a substance by a fluid due to the fluid's bulk motion.

4 Diffusion is the movement of a substance from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration.

5 A graben is a depressed block of land bordered by parallel faults.

6 The condensation of coastal fog may account for a substantial portion of the water consumption of typical cloud forests. In extreme cases, it could exceed the amount of measured precipitation (Kiss and Bräuning, 2008).

7 A lineament is a linear feature of a landscape which expresses the location of an underlying geological structure such as a fault. Fracture zones and igneous intrusions such as dikes can also give rise to lineaments.

8 The Quaternary Period is the current and most recent period of the Cenozoic Era. It follows the Neocene Period and spans from 2.588 million years to the present.

9 In fluid mechanics, a control volume is a mathematical abstraction employed in the process of creating mathematical models of physical processes. In a fixed frame of reference, it is a volume in space through which the fluid flows. Unlike fluid mechanics, in groundwater flow the choice of control volume is not clearly defined, varying with the extent of capture; see, for instance, Prudic and Herman (1996).

10 In a seminal paper widely credited with originating the scientific study of groundwater, Theis (1940) wrote: "It is evident that on the average the rate of discharge from the aquifer during recent geologic time has been equal to the rate of input into it... Under natural conditions, therefore, previous to development by wells, aquifers are in a state of approximate dynamic equilibrium. Discharge by wells is thus a new discharge superimposed upon a previously stable system, and it must be balanced by an increase in the recharge of the aquifer, or by a decrease in the old natural discharge, or by a loss of storage in the aquifer, or by a combination of these." (Author's emphasis) (See Fig. 32).

11

By way of comparison,

the total volume of groundwater pumping in the United States has been estimated to be

about

12 Mesophytes are terrestrial plants which are adapted to neither a particularly dry nor particularly wet environment. In arid and semiarid landscapes, mesophytes populate the areas close to sources of exfiltrating water, like springs and depressions.

REFERENCES

Alley, W. M., T. E. Reilly, and. O. E. Franke. 1999. Sustainability of groundwater resources. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1186, Denver, Colorado, 79 p.

Beatty, S. W. 1984. Vegetation and soil patterns in Southern California chaparral communities. In B. Dell, editor, Medecos IV: Proceedings, 4th International Conference on Mediterranean Ecosystems, August 13-17, 1984, The Botany Department, University of Western Australia, Nedlands, Australia, 4-5.

Bolin, B. 1970. The carbon cycle. Scientific American, Vol. 223, No. 3, September, 124-132.

Brown, O. 1923. The Salton Sea Region, California: A geographic, geologic, and hydrologic reconnaisance with a guide to desert watering places." U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 497.

Chebotarev, I. I. 1955. Metamorphism of natural waters in the crust of weathering. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, Vol. 8, 22-48, 137-170, 198-212.

Freeze, R. A., and J. A. Cherry. Groundwater. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey.

Hanes, T. L. (1965). Ecological studies of two closely related chaparral shrubs in Southern California. Ecological Monographs, 35(2), 213-235. Galloway, D., D. R. Jones, and S. E. Ingebritsen. 2013. Land subsidence in the United States. U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1182, U.S. Department of Interior, Washington, D.C.

Jones, A. A. 1997. Global hydrology: Processes, resources, and environmental management. Longman, England.

L'vovich, M. I. 1979. World water resources and their future. Translation from Russian by Raymond L. Nace, American Geophysical Union.

Maimone, M. 2004. Defining and managing sustainable yield. Ground Water, Vol. 42, No.6, November-December, 809-814. Meinzer, O. E. 1927. Plants as indicators of ground water. U.S. Geological Survey Water Supply Paper 577.

Ponce, V. M., and C. N. da Cunha. 1993. Vegetated earthmounds in tropical savannas of Central Brazil: A synthesis; with special reference to the Pantanal of Mato Grosso. Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 20, 219-225.

Ponce, V. M. 1995. Management of floods and droughts in the semiarid Brazilian Northeast: The case for conservation. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, Vol. 50, No. 5, September-October, 422-431.

Ponce, V. M., A. K. Lohani, and P. T. Huston. 1997. Surface albedo and water resources: Hydroclimatological impact of human activities. ASCE Journal of Hydrologic Engineering, Vol. 2, No. 4, October, 197-203.

Ponce, V. M., R. P. Pandey, and S. Ercan. 2000. Characterization of drought across climatic spectrum. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering, ASCE, Vol. 5, No. 2, April, 222-224.

Ponce, V. M. 2006. Impact of the proposed Campo landfill on the hydrology of the Tierra del Sol watershed: A reference study. Online report, May.

Ponce, V. M. 2007. Sustainable yield of groundwater. Online article.

Ponce, V. M. 2011. The 800-mm isohyet. Online article.

Ponce, V. M. 2012a. The salinity of groundwaters. Online article.

Ponce, V. M. 2012b. Thompson Creek groundwater sustainability study. Online report.

Seward, P., Y. Xu, and L. Brendock. (2006). Sustainable groundwater use, the capture principle, and adaptive management. Water SA, Vol. 32, No. 4, October, 473-482.

Shreve, F. 1934. The problems of the desert. The Scientific Monthly, 38(3), March, 199-209.

Theis, C. V. 1940. The source of water derived from wells: Essential factors controlling the response of an aquifer to development. Civil Engineering, Vol 10, No. 5, May, 277-280.

World Water Balance and Water Resources of the Earth. 1978. U.S.S.R. Committee for the International Hydrological Decade, UNESCO, Paris, France. |

| 210701 16:45 |